Understanding the Terrain: Markets and Purchasing Behaviour

Consumer Market Behaviour

We begin our analysis of the decisions and acts people undertake to buy products or services for personal use by reviewing the exchange process.

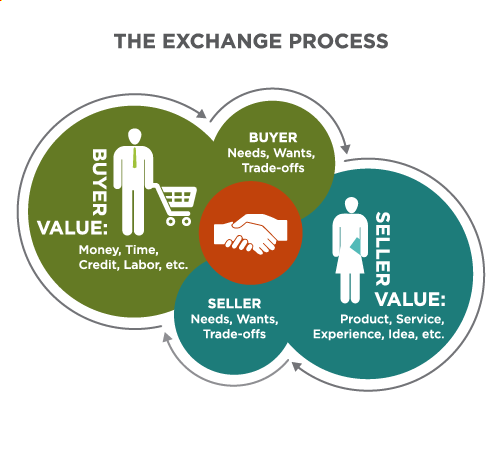

The Exchange Process

As introduced in Chapter 1, the exchange process is a key element of consumer buying behaviour, as it provides the context for the interactions and transactions that occur between buyers and sellers. This is a fundamental concept in marketing that involves the act of obtaining a desired object from someone by offering something of value in return.

A successful exchange takes place when its key elements are aligned: the respective needs, wants, trade-offs, and value exchanged by the buyer and seller.

To understand the dynamics of the exchange process, it is helpful to take a closer look at the buyer (consumer) and how they make buying decisions. Several theories have been developed to help understand how consumers make decisions.

Here are two contrasting models:

- The economic man theory

- The stimulus-response model

The Economic Man Theory of Consumer Behaviour

The economic man theory[1] is an early model of consumer decision-making based on principles of economics.

This theory assumes consumers:

- Are rational and self-interested individuals.

- Make decisions based on complete knowledge of all available options.

- Seek to maximize the benefits they derive from the exchange process.

Criticisms of the Economic Man Theory

Criticisms of the economic man theory include:

- Overly Simplistic: The theory is criticized for oversimplifying human behaviour, ignoring emotional and social factors that influence decision-making.

- Limited Information: In reality, consumers often lack complete information about all available options, leading to less-than-optimal decisions.

- Irrational Behaviour: Consumers frequently make irrational decisions based on emotions, cognitive biases, and social conventions rather than pure rationality.

The Stimulus-Response Model of Consumer Behaviour

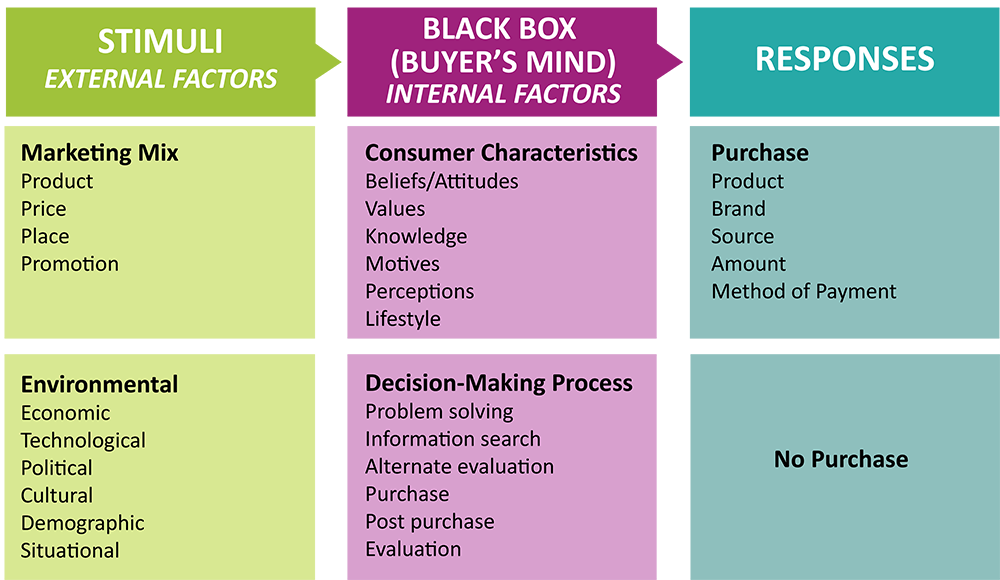

The stimulus-response model of consumer behaviour, also known as the “black box model,”[2] is a framework used to understand how consumers make purchasing decisions. This model assumes that consumer behaviour is a response to various stimuli, which can be external or internal, and that these stimuli are processed in the consumer’s “black box” — a metaphor for the internal thought processes that influence decision-making.

Key Components of the Stimulus-Response Model

The three key components of the stimulus-response model are:

- Stimuli:

- Marketing Stimuli: These include the 4 Ps — product, price, place, and promotion. Marketers use these elements to influence consumer behaviour.

- Environmental Stimuli: These encompass broader factors such as economic conditions, cultural influences, social factors, and technological changes.

- The Black Box: The black box represents the internal processes of the consumer, including psychological and personal characteristics that affect how stimuli are perceived and processed. This includes factors like motivation, perception, attitudes, and beliefs.

- Response: The outcome of the stimuli processing in the black box is the consumer’s response, which can include product choice, brand selection, purchase timing, and purchase amount.

How the Model Works

The model suggests that marketers can influence consumer behaviour by manipulating the marketing stimuli that enter the black box. However, understanding what happens inside the black box — how consumers process these stimuli — is crucial for predicting their responses. This involves studying consumer psychology and behaviour to tailor marketing strategies that appeal to consumers’ needs and preferences.

Let’s take a closer look at the buyer’s mind or “black box”.

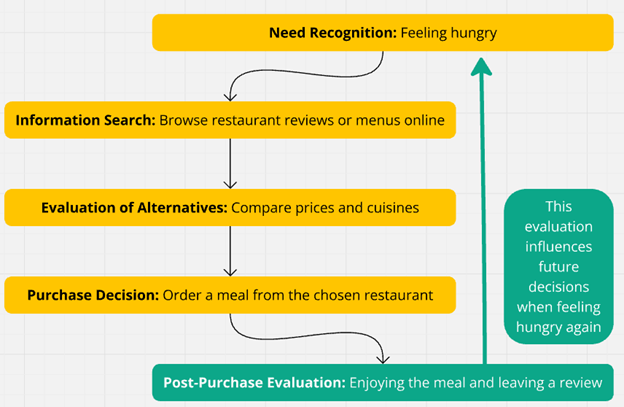

The Consumer Decision-Making Process

The consumer decision-making process is a series of stages that consumers go through when deciding to purchase a product or service. This process is commonly depicted as a five-stage model[3]:

- Need Recognition: The process begins when a consumer recognizes a need or problem that requires a solution. This recognition can be triggered by internal factors (e.g., hunger and thirst) or external factors (e.g., advertising and situational influences).

- Information Search: After recognizing a need, consumers seek information about potential solutions. This involves gathering data from various sources, such as online searches, reviews, advertisements, word-of-mouth recommendations, and/or past experience.

- Evaluation of Alternatives: Consumers compare different products or services to determine which best meets their needs. They consider factors such as price, quality, features, and brand reputation during this evaluation phase.

- Purchase Decision: After evaluating alternatives, the consumer makes a decision and proceeds to purchase the chosen product or service. This decision can be influenced by additional factors such as promotions, discounts, or peer recommendations.

- Post-Purchase Evaluation: After the purchase, consumers reflect on their decision and the product’s performance. This stage involves assessing satisfaction, which can influence future purchasing behaviour and brand loyalty.

Consumer Buying Behaviours

The consumer decision-making process will look differently for different consumers and purchases due to several factors. The process may take more or less time depending on the consumer characteristics, the nature of the need or problem to be solved, and the external factors.

Level of Involvement

How involved a consumer is when making a purchasing decision can be classified as high or low.

High Involvement

Some purchase decisions require high involvement on behalf of the buyer. They are typically important to the buyer and may be closely tied to the consumer’s ego and self-image. They may involve some risk to the consumer such as:

- Financial risk (e.g., highly priced items)

- Social risk (e.g., products that are important to the peer group)

- Psychological risk (e.g., the wrong decision may cause the consumer some concern and anxiety)

Low Involvement

Some purchase decisions require low-involvement on behalf of the buyer. They are typically straightforward decisions, require little risk, are not very important to the consumer, or are repetitive and often lead to a habit.

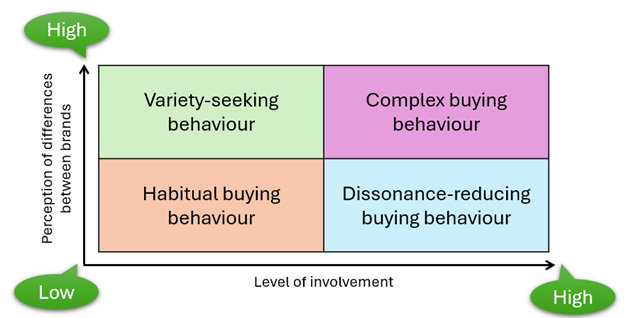

Types of Consumer Buying Behaviour

To help us understand the possible range of buying behaviours, we classify consumer buying behaviours into four main types according to the level of consumer involvement needed and the perceived differences among brands:

- Complex buying behaviour

- Dissonance-reducing buying behaviour

- Habitual buying behaviour

- Variety-seeking buying behaviour

Examples

Types of Consumer Buying Behaviours

Complex Buying Behaviour: Complex buying behaviour occurs when consumers are highly involved in the purchase decision, often because the product is expensive, infrequently purchased, or risky. Consumers perceive significant differences among brands and engage in extensive research before making a decision.

Example: Purchasing a new car involves complex buying behaviour. Consumers evaluate various factors such as safety features, fuel efficiency, brand reputation, and price. They often conduct online research, take test drives, and consult with friends or experts before making a final decision.

Dissonance-Reducing Buying Behaviour: Dissonance-reducing buying behaviour occurs when consumers are highly involved in the purchase but see little difference among brands. This often leads to post-purchase dissonance, where consumers seek reassurance that they made the right choice.

Example: A couple is planning their honeymoon and decides to book an all-inclusive resort vacation in the Caribbean. This is a high-involvement purchase for them, as it is an expensive and significant trip to celebrate their marriage. However, as they research different resorts, they find that many offer similar amenities, activities, and pricing structures. After spending considerable time comparing options, they finally choose Resort A.

However, even after booking, they experience some anxiety and doubt about their decision:

-

- Did they pick the best resort for their needs?

- Would Resort B have been a better choice?

- Will the food and service meet their expectations?

To reduce this dissonance, the couple might:

-

- Seek out positive reviews and testimonials from past guests of Resort A.

- Focus on the unique features that made them choose Resort A in the first place.

- Avoid looking at promotions or deals for other resorts they did not choose.

- Reach out to the resort directly to confirm details and ask questions, seeking reassurance about their choice.

The resort, recognizing this common behaviour, might employ strategies to reduce dissonance:

-

- Sending a personalized welcome email highlighting the resort’s best features.

- Providing a detailed itinerary of activities and dining options.

- Offering a virtual tour or photo gallery to build excitement.

- Assigning a dedicated concierge to address any concerns before arrival.

Habitual Buying Behaviour: Habitual buying behaviour is characterized by low consumer involvement and minimal perceived differences among brands. Purchases are made out of habit rather than brand loyalty or detailed evaluation.

Example: The purchase of everyday items like salt or sugar often involves habitual buying behaviour. Consumers tend to buy the same brand regularly without much thought unless a disruption occurs, such as a stock shortage.

Variety-Seeking Buying Behaviour: Variety-seeking buying behaviour occurs when consumers have low involvement but perceive significant differences among brands. They often switch brands for the sake of novelty or change.

Example: When buying snacks, consumers might switch brands simply to try something new, even if they are satisfied with their current choice.

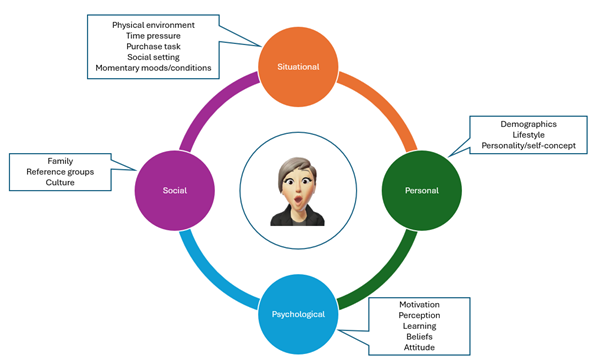

Factors Influencing Consumer Decisions

As we learned from the stimulus-response model, consumer buying decisions are influenced by a complex interplay of various external and internal factors. This section takes a closer look at the factors that shape the consumer’s purchasing behaviour:

- Situational factors

- Personal factors

- Psychological factors

- Social factors[4]

Situational Factors

Situational factors are generally temporary conditions that can influence consumer behaviour at the point of purchase[5].

These temporary conditions may be related to the:

- Physical environment (location, layout, lighting, parking, weather, etc.)

- Time pressure (time available, time of day, season, etc.)

- Purchase purpose or task definition (for self, gift, high/low level of involvement, etc.)

- Social surroundings (ambiance, level of crowding, queues, etc.)

- State of mind or antecedent states (momentary moods or conditions — such as happy, tired, anxious, frustrated — credit card balance available, etc.).

Example

Situational Factors Impacting Consumer Behaviour: The Case of the Coffee Shop

Imagine a busy professional, Sarah, who usually enjoys a latte on her way to work. She typically visits a specific coffee shop near her office, known for its consistent quality and friendly staff. However, one morning, a major traffic jam delays Sarah’s commute.

Situational Factors at Play:

- Time Pressure: The traffic jam significantly increases Sarah’s time pressure. She is now running late for work and needs to make a quick decision.

- Physical Surroundings: Sarah finds herself in a new area, unfamiliar with the coffee shops nearby. The lack of her usual coffee shop and the unfamiliar surroundings create a sense of uncertainty.

- Social Surroundings: Sarah notices a long queue at a nearby coffee shop, filled with people in a hurry. This creates a sense of urgency and reinforces the need for a quick purchase.

Impact on Consumer Behaviour:

- Reduced Consideration: Sarah is less likely to spend time comparing different coffee shops or considering different drinks. She prioritizes speed and convenience.

- Impulsive Purchase: Faced with time pressure and unfamiliar surroundings, Sarah might opt for the first coffee shop she encounters, even if it is not her usual choice.

- Limited Choice: Sarah might settle for a simpler drink, like a black coffee, instead of her usual latte, as it is faster to prepare.

Outcome

Due to the situational factors, Sarah’s usual coffee routine is disrupted. She makes a quick, impulsive purchase, opting for convenience over her usual preferences. This illustrates how situational factors can significantly influence consumer behaviour, even for seemingly simple decisions like buying a cup of coffee.

Personal Factors

Personal factors are characteristics unique to each individual, such as age, occupation, economic situation, lifestyle, personality, and self-concept.

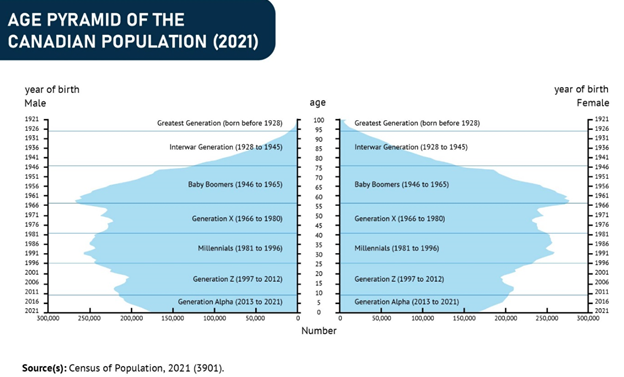

Demographic

Demographic factors are personal factors that can be measured and/or observed, such as age, gender, education, occupation, marital status, family structure, life stage, ethnicity, geographic location, and income. These are factors that are used to study the composition of populations.

Example

The Age Pyramid of the Canadian Population

The age pyramid of the Canadian population reveals the size and distribution of age groups, providing key insights into consumer behaviour. It helps identify market potential, such as increased demand for senior-focused products in an aging population or technology for younger cohorts.

Lifestyle

Lifestyle refers to a person’s pattern of living as expressed through their activities, interests, and opinions (AIOs):

- Activities: How consumers spend their time (e.g., work, hobbies, sports, shopping).

- Interests: What consumers consider important in their environment (e.g., family, home, food, fashion).

- Opinions: How consumers view themselves and the world around them (e.g., social issues, politics, business).

Example

Impact of Lifestyle on Purchasing Decisions

Different lifestyles lead to different purchasing patterns. For example:

- Outdoor Enthusiasts: Likely to invest more in camping gear, hiking boots, or mountain bikes.

- Health-Conscious Consumers: May spend more on organic foods, gym memberships, or fitness trackers.

- Tech-Savvy Individuals: Might prioritize spending on the latest gadgets and smart home devices.

- Eco-Friendly Consumers: Often choose products with sustainable packaging or from brands with strong environmental policies.

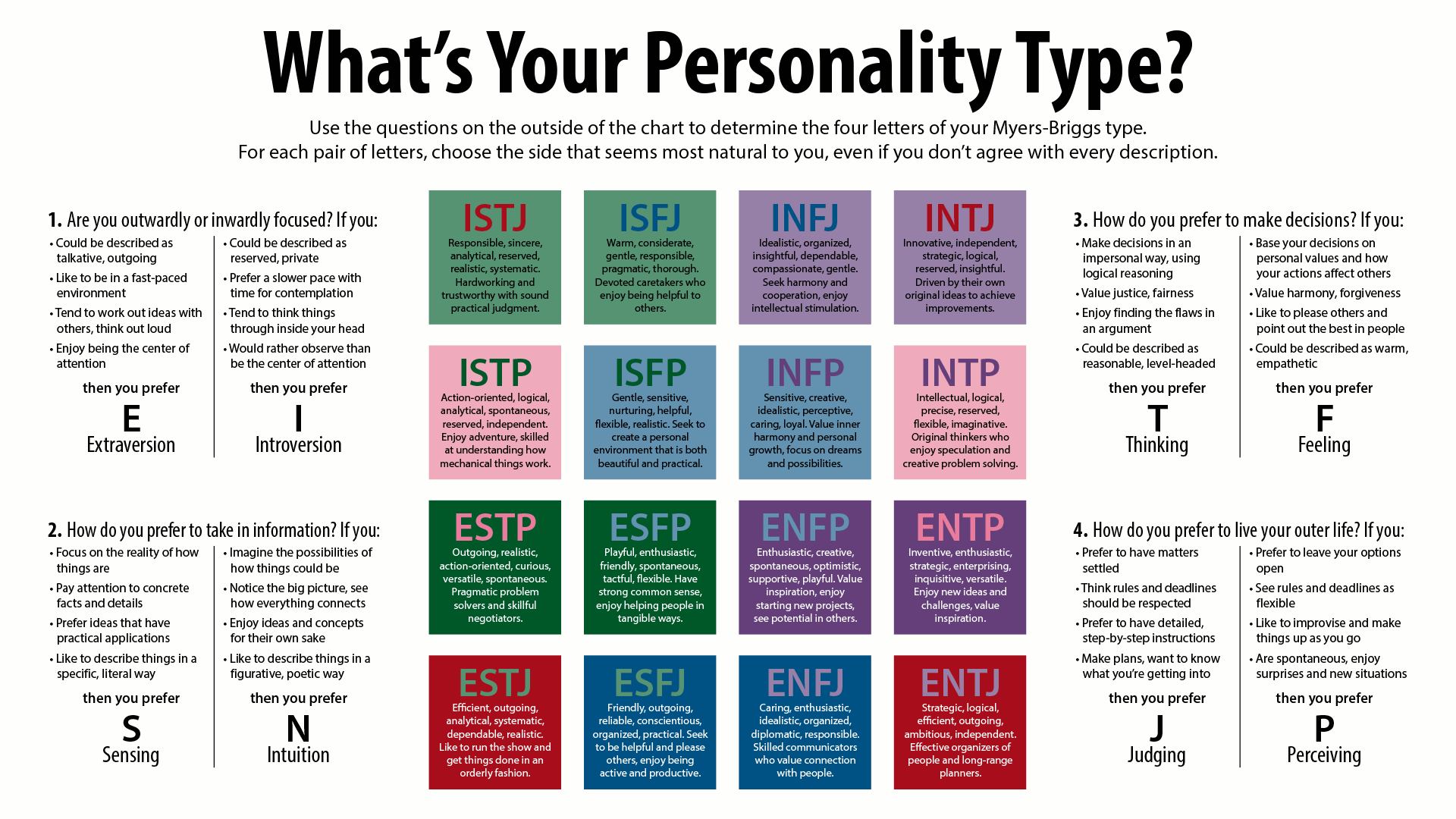

Personality and Self-Concept

Individual personality traits and how consumers view themselves (i.e., self-concept) affect their brand choices and purchasing behaviour.

Examples

How Personality and Self-Concept Can Influence Consumer Decisions

Below shows how a person’s personality and self-concept play a role in their consumer decisions.

Personality Traits

The Big Five personality traits[6] have been shown to correlate with certain consumer behaviours and preferences:

- Openness to Experience:

- More likely to try new products and brands

- Attracted to novel and unique offerings

- Tend to be early adopters of new technologies

- Conscientiousness:

- More likely to research products thoroughly before purchasing

- Tend to prefer reliable, high-quality brands

- May be less impulsive in buying decisions

- Extraversion:

- More influenced by social factors in purchasing decisions

- Drawn to brands with outgoing, exciting personalities

- May engage in more conspicuous consumption

- Agreeableness:

- More likely to be influenced by recommendations from others

- Tend to prefer brands perceived as ethical or socially responsible

- May be more loyal to familiar brands

- Neuroticism:

- More prone to emotional and impulsive purchasing

- May be more susceptible to fear-based marketing tactics

- Tend to seek products that provide comfort or security

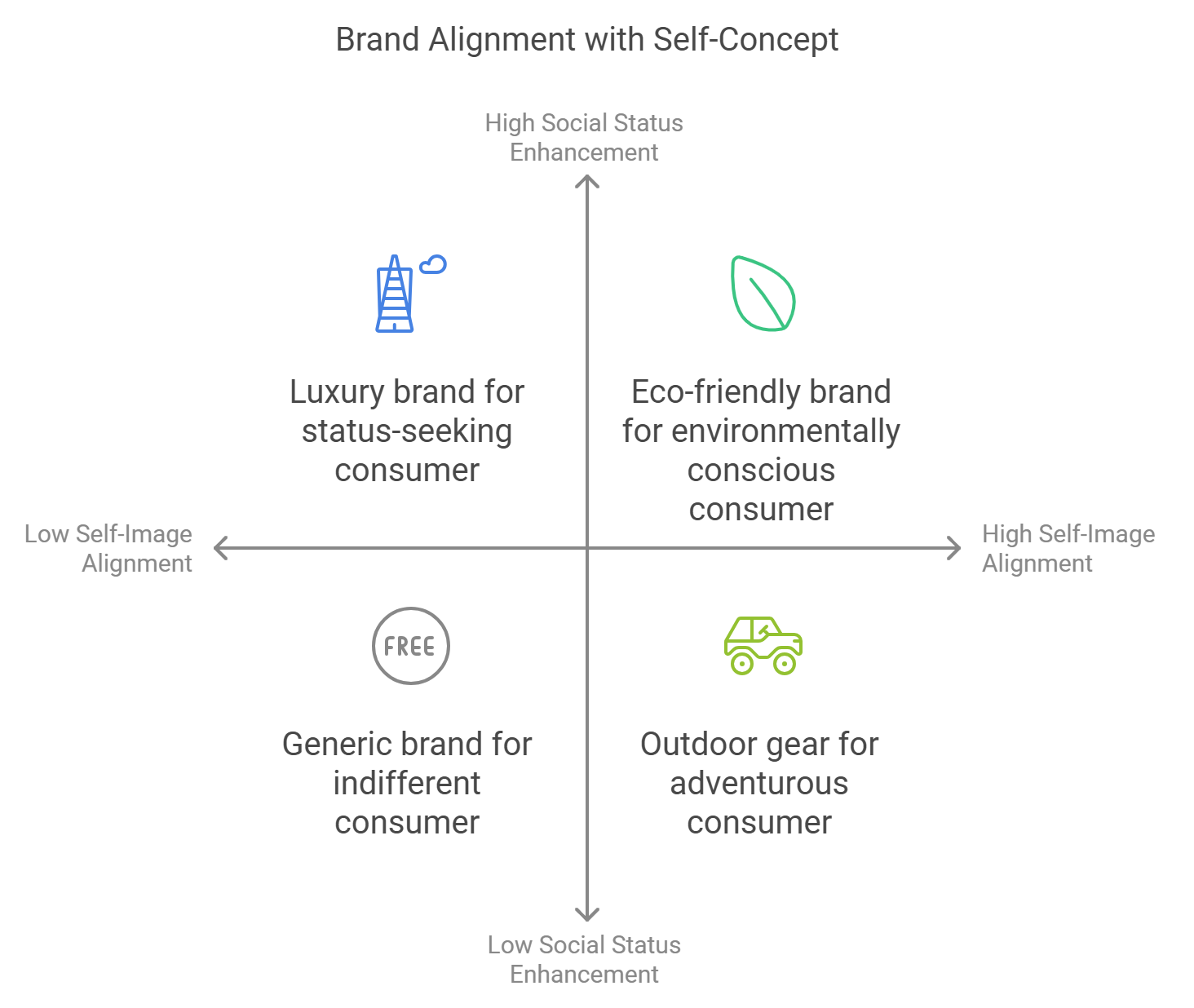

Self-Concept

People tend to purchase products that reflect their actual or ideal self-concept[7]

Consumers often choose brands and products that align with or enhance their self-image:

- Brands can be used to express one’s identity or values

- Consumers may avoid brands that conflict with their self-image

- Products can be used to reinforce or elevate one’s social status

For example, someone who views themselves as environmentally conscious may prefer eco-friendly brands, while someone who sees themselves as adventurous may be drawn to outdoor gear brands.

Psychological Factors

Psychological factors include motivation, perception, learning, beliefs, and attitude. These are internal influences that originate within the individual.

Motivation

Motivation is a fundamental driver of consumer behaviour, shaping how individuals make purchasing decisions and interact with brands. It encompasses the internal psychological processes that drive consumers to take specific actions to satisfy their needs and desires.

Theories of Motivation

Two prominent theories help explain consumer motivation:

- Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

- Herzberg’s two-factor theory

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

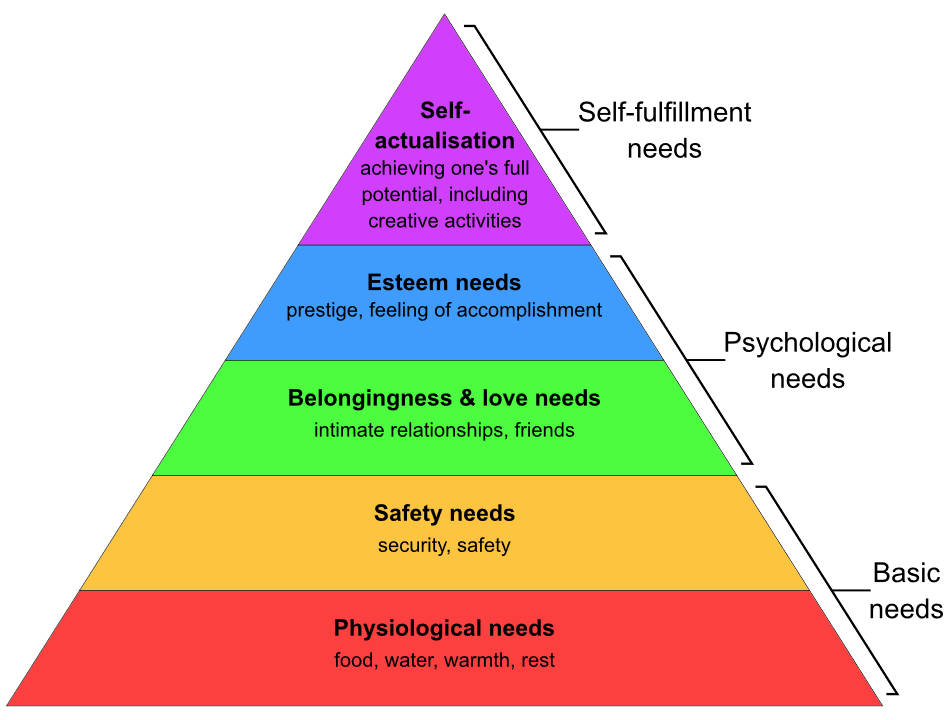

Maslow's hierarchy of needs[8] explains why people are driven by particular needs at specific times. We examined Maslow’s theory in Chapter 1 as part of the core marketing concepts. To recap, the model proposes that human needs are arranged in a hierarchy: physiological needs at the base, followed by safety needs, love and belonging needs, esteem needs, and finally self-actualization needs.

According to this theory, lower-level needs must be satisfied before higher-level needs can influence behaviour. For example, a consumer might first focus on purchasing food and shelter (physiological and safety needs) before seeking products that fulfill social or esteem needs, such as branded clothing or luxury items.

Example

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory and the Restaurant Experience

Here is an example of how Maslow’s hierarchy of needs can be applied to a restaurant experience addressing each level of the hierarchy to enhance customer satisfaction and loyalty:

Physiological Needs: The restaurant provides high-quality food and beverages, ensuring that basic hunger and thirst are satisfied. This is the most fundamental level, where the focus is on offering nutritious and delicious meals.

Safety Needs: The restaurant ensures a safe and clean environment, including proper hygiene standards in food preparation and a secure dining area. Customers feel safe and protected, which is crucial for their comfort and peace of mind.

Love and Belonging Needs: The restaurant fosters a welcoming atmosphere where customers feel a sense of belonging. This can be achieved through friendly staff interactions, creating a community vibe, or hosting events that encourage socializing among patrons.

Esteem Needs: The restaurant enhances customers’ self-esteem by providing exceptional service and recognizing regular patrons. This could include personalized greetings, remembering customers’ preferences, or offering loyalty programs that make them feel valued and respected.

Self-Actualization Needs: The restaurant offers unique dining experiences that allow customers to explore new cuisines or engage in culinary classes. This level is about providing opportunities for personal growth and fulfilling experiences, such as themed nights or chef’s table events that inspire creativity and learning.

By addressing each level of Maslow’s hierarchy, a restaurant can create a comprehensive experience that meets the diverse needs of its customers, leading to greater satisfaction and repeat business.

Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory[9]

Herzberg's two-factor theory, originally developed for workplace motivation, can be applied to explain consumer behaviour in marketing contexts. This adaptation provides valuable insights into what drives customer satisfaction and loyalty.

Herzberg’s theory distinguishes between two types of factors:

- Dissatisfiers (Hygiene Factors): These are basic expectations that, if absent, can cause dissatisfaction but do not necessarily motivate when present. Examples include basic product quality and reliability, fair pricing, standard customer service, ease of use, and accessibility.

- Satisfiers (Motivators): These are factors that can actively motivate consumers. Examples include product innovation and exceptional service.

Example

Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory and the Restaurant Experience

When applied to a restaurant experience, Herzberg’s two-factor theory can help explain customer satisfaction and motivation. Here is an example of how the theory’s two factors — hygiene factors and motivators — might play out in a restaurant setting:

Hygiene Factors (Dissatisfiers):

- Cleanliness: Clean tables, utensils, and restrooms. If these are not up to standard, it will cause dissatisfaction.

- Food Safety: Properly cooked and handled food. Customers expect this as a basic requirement.

- Reasonable Prices: Prices that align with the restaurant’s category and location.

- Comfortable Seating: Chairs and tables that are in good condition and comfortable.

- Adequate Lighting: Proper illumination throughout the restaurant.

- Polite Staff: Basic courtesy from servers and other staff members.

- Reasonable Wait Times: Not having to wait an excessively long time for food or service.

When present, these factors do not necessarily increase satisfaction, but their absence can lead to dissatisfaction.

Motivators (Satisfiers):

- Exceptional Food Quality: Dishes that exceed expectations in taste and presentation.

- Unique Menu Items: Innovative or signature dishes that cannot be found elsewhere.

- Personalized Service: Staff who remember regular customers’ preferences or offer tailored recommendations.

- Ambiance: A particularly pleasing atmosphere or decor that enhances the dining experience.

- Chef Interaction: Opportunities to meet the chef or watch food preparation.

- Special Touches: Complimentary amuse-bouche or after-dinner mints.

- Recognition: Staff acknowledging special occasions like birthdays or anniversaries.

When present, these factors can lead to high levels of satisfaction and customer loyalty.

In this context, a restaurant might find that simply meeting hygiene factors (e.g., having clean tables and polite staff) does not guarantee customer satisfaction. To truly delight customers and motivate return visits, they need to focus on motivators like exceptional food quality or unique dining experiences. However, neglecting hygiene factors (e.g., having dirty restrooms or rude staff) can lead to customer dissatisfaction regardless of how good the motivators are.

This application of Herzberg’s theory can help restaurant managers understand why customers might be dissatisfied despite good food (hygiene factors not met) or why customers might not be particularly excited about their experience despite everything being “fine” (lack of motivators).

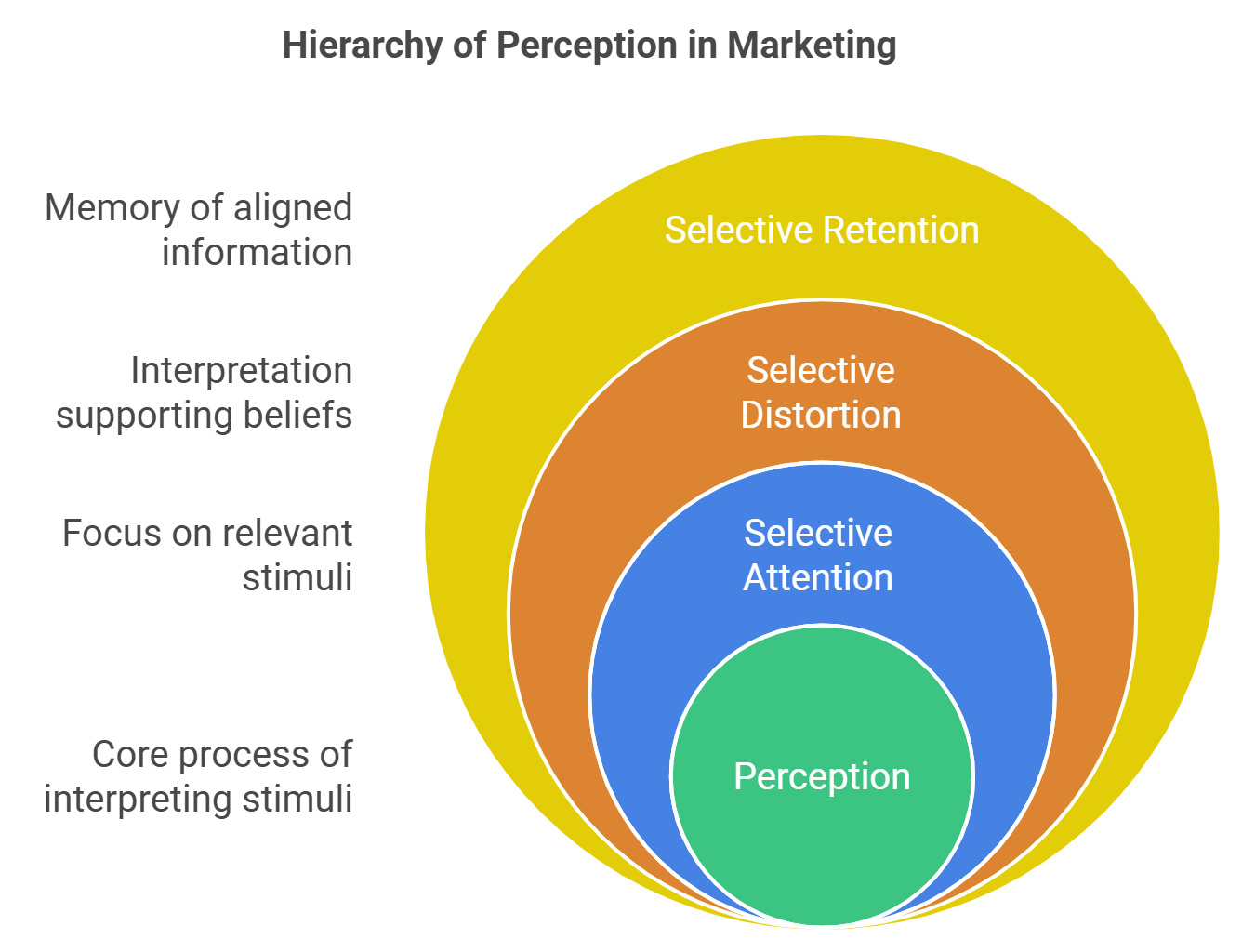

Perception

Perception is the process by which individuals select, organize, and interpret stimuli to form a meaningful picture of the world around them. In the context of marketing and consumer behaviour, perception plays an important role in how customers interpret and respond to marketing messages, products, and services.

Key aspects of perception include:

- Selective Attention: Consumers tend to notice stimuli that relate to their current needs or interests.

- Selective Distortion: People interpret information in a way that supports their existing beliefs.

- Selective Retention: Individuals are more likely to remember information that aligns with their attitudes and beliefs.

Examples

Perception

Selective Attention: A consumer planning a vacation might notice advertisements for travel agencies, airlines, or hotels more than usual. This is because these advertisements relate to their current need to plan a trip. In contrast, they might ignore ads for unrelated products, such as home appliances, because those do not align with their immediate interests.

Selective Distortion: Consider a consumer who strongly believes that a particular brand of smartphone is superior. When they read a review that highlights both positive and negative aspects of this smartphone, they might focus on the positive comments and downplay the negatives. This selective distortion occurs because they interpret the information in a way that supports their existing belief in the brand’s superiority.

Selective Retention: A consumer who is environmentally conscious might remember advertisements or product information that emphasize eco-friendly features. For instance, they are more likely to recall details about a hotel’s sustainability practices or a car’s fuel efficiency, as these align with their attitudes and beliefs about environmental responsibility. Conversely, they might forget other product details that do not support their environmental values.

Figure 12 illustrates the hierarchy of perception in marketing, depicting perception progressing through four stages:

- Perception

- Selective attention

- Selective distortion

- Selective retention

Each stage builds upon the previous one, highlighting the core process of interpreting stimuli, focusing on relevant stimuli, interpreting information to support beliefs, and retaining aligned information in memory.

Learning

Learning in consumer behaviour refers to the process through which consumers acquire information and experience about a product or service, which subsequently influences their purchasing decisions. This learning can be experiential, such as using a product and finding it satisfactory, or informational, such as learning about a product through advertisements or reviews.

Examples

Learning

Experiential Learning Through Hotel Stays: A traveler’s direct experience staying at different types of accommodations shapes their future booking decisions. When guests have a positive experience at a boutique hotel, including personalized service and unique amenities, they learn through first-hand experience what they value in accommodations. This experiential learning influences their future hotel selections and willingness to pay premium rates for similar experiences.

Guided Cultural Tours: Tourists learn about destinations through guided tours that provide both informational and experiential learning opportunities. As visitors engage with local history and culture through expert guides, they develop a deeper understanding and appreciation that influences their future travel choices. This type of learning can lead to increased interest in cultural tourism and influence decisions about future destination selections.

Beliefs

Beliefs are the convictions that consumers hold about a product or brand. These beliefs can be based on personal experiences, advertising, word-of-mouth, or cultural influences. They shape how consumers perceive products and influence their purchasing decisions.

Example

Beliefs

A consumer who believes that organic foods are healthier may prefer purchasing organic products over non-organic ones. This belief influences their buying behaviour by guiding them towards products that align with their health values.

Attitude

An attitude describes a person’s relatively consistent evaluations, feelings, and tendencies toward an object or an idea. Attitudes are a combination of beliefs, feelings, and behavioural intentions towards a product or service. They are formed over time and can significantly influence consumer behaviour. Positive attitudes towards a brand can lead to increased loyalty and repeat purchases, while negative attitudes can deter consumers from buying.

Example

Attitude

A consumer with a positive attitude towards a brand known for its environmental sustainability may be more inclined to purchase from that brand, even if the products are priced higher than competitors. This attitude is shaped by the consumer’s values and the brand’s alignment with those values.

Social Factors

Social factors can be categorized into influences from family, reference groups, and culture. Below is a detailed look at each.

Family

Family is one of the most influential social factors affecting consumer behaviour. It plays a crucial role in shaping an individual’s buying preferences and decisions:

- Influence on Preferences: From a young age, individuals develop preferences by observing their family’s purchasing habits. For example, a person might continue buying the same brand of cereal their parents bought during childhood.

- Decision-Making Dynamics: Family roles and dynamics, such as who has the final say in purchasing decisions, can significantly impact buying behaviour. For instance, children may influence parents’ purchases of toys or snacks, while spouses might make joint decisions on larger purchases like cars or homes.

Reference Groups

Reference groups are groups of people that an individual looks to for guidance on social norms, values, and behaviours. These groups can include family members, friends, coworkers, or even celebrities:

- Influence through Comparison: Individuals often compare themselves to members of their reference groups and may be influenced by their opinions and actions. For example, a person might choose a particular brand of clothing because it is popular among their peer group.

- Types of Reference Groups: They can be primary groups, such as family and close friends, or secondary groups, like professional associations or clubs. The influence can be direct, through face-to-face interaction, or indirect, through social media or other channels.

Reference groups can significantly impact consumer choices through peer pressure and social comparison, especially in the age of social media where influencers and online communities play a prominent role.

Culture

Culture encompasses the shared beliefs, values, customs, and behaviours of a group or society. It profoundly shapes consumer behaviour by:

- Defining Norms: Culture influences what products are considered necessary or desirable, how they are purchased, and what they signify socially.

- Subcultures: Within larger cultures, subcultures form around shared interests or characteristics, such as ethnicity or geography. These subcultures can lead to strong brand loyalty if a brand aligns with their values.

- Cultural Practices: Different cultures have unique practices, such as haggling over prices or preferring fixed pricing, which can influence buying behaviour.

Examples

Cultural Dimensions

Hofstede's cultural dimensions theory[10] is a framework developed by Geert Hofstede to understand cultural differences across countries and their impact on behaviour and values. This theory identifies six dimensions that describe different aspects of national cultures. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory is a valuable tool for understanding consumer purchasing behaviour because it provides a framework for analyzing how cultural differences influence consumer values and behaviours.

Here is a summary of the dimensions and their key aspects:

Individualism vs. Collectivism: This dimension examines whether a culture values individual achievements and independence or prioritizes group harmony and community. In individualistic cultures, consumers may make purchasing decisions based on personal preferences and benefits, while in collectivist cultures, decisions might be influenced by family or community opinions.

Power Distance: This dimension measures the extent to which less powerful members of a society accept and expect power to be distributed unequally. In high power distance cultures, consumers may be more influenced by authority figures and hierarchical structures, impacting their brand choices and loyalty.

Uncertainty Avoidance: This dimension reflects a culture’s tolerance for ambiguity and uncertainty. In cultures with high uncertainty avoidance, consumers may prefer well-established brands and products with clear benefits, as they seek to minimize risk.

Masculinity vs. Femininity: This dimension looks at the distribution of roles between genders in a society. Masculine cultures value competitiveness and achievement, which can influence consumer preferences for status-driven products. Feminine cultures prioritize quality of life and care for others, affecting preferences for products that emphasize these values.

Long-term vs. Short-term Orientation: This dimension considers the degree to which a culture emphasizes future rewards over short-term benefits. Long-term oriented cultures may favor products that offer long-term value and sustainability, while short-term oriented cultures might prioritize immediate gratification.

Indulgence vs. Restraint: This dimension assesses the extent to which a culture allows or suppresses gratification of desires. Indulgent cultures may have consumers who are more willing to spend on luxury and leisure, while restrained cultures might focus on necessity and practicality.

Learn about differences across cultures by using the Country Comparison Tool available through the Culture Factor website[11].

Media Attributions

- Figure 1: “The Exchange Process” by Lumen Learning (2024), in Principles of Marketing, is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Figure 2: “Figure 1. Black Box Model” by Lumen Learning (2024), in Principles of Marketing, is used under a CC BY 4.0 license

- Figure 3: “The consumer decision-making process” [created using Miro] by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 4: “Types of consumer buying behaviours” [created using Microsoft PowerPoint] by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 5: “Factors influencing consumer decisions” [created using Microsoft PowerPoint] by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 6: “Age Pyramid of the Canadian population (2021)” by Statistics Canada (2022) is reproduced and distributed on an “as is” basis with permission.

- Figure 7: “Man in black t-shirt and black shorts running on road during daytime” by Gabin Vallet (2020), via Unsplash, is used under the Unsplash license.

- Figure 8: “MyersBriggsTypes” by Jake Beech (2014), via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

- Figure 9: “Brand alignment with self-concept” [created using Napkin.ai] by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 10: “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs” by AndroidMarsExpress (2020), via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 11: “People at restaurant” by Nick Hillier (2017), via Unsplash, is used under the Unsplash license.

- Figure 12: “Hierarchy of perception in marketing” [created using Napkin.ai] by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 13: “Five group of men sitting together with their skateboards” by Parker Gibbons (2018), via Unsplash, is used under the Unsplash license.

- Figure 14: “People Crowd Group” by geralt, via Pixabay, is used under the Pixabay content license.

- Persky, J. (1995). The ethology of homo economicus. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(2): 221–231. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.9.2.221 ↵

- Kotler, P. (1965). Behavioral models for analyzing buyers. Journal of Marketing, 29(4), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224296502900408 ↵

- Blackwell, R. D., Miniard, P. W., & Engel, J. F. (2006). Consumer behavior (10th ed.). Thomson/South-Western. ↵

- Solomon, M. R. (2020). Consumer behavior: Buying, having, and being (13th ed.). Pearson. ↵

- Belk, R. W. (1975). Situational variables and consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 2(3), 157–164. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2489050 ↵

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1987). Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81 ↵

- Shavelson, R. J., Hubner, J. J., & Stanton, G. C. (1976). Self-concept: Validation of construct interpretations. Review of Educational Research, 46(3), 407–441. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543046003407 ↵

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346 ↵

- Lian Chan, J. K., & Baum, T. (2007). Researching consumer satisfaction: An extension of Herzberg’s motivator and hygiene factor theory. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 23(1), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v23n01_06 ↵

- Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014 ↵

- The Culture Factor Group. (n.d.). Country comparison tool. Retrieved November 26, 2024, from https://www.theculturefactor.com/country-comparison-tool ↵

The act of obtaining a desired object from someone by offering something of value in return.

An early model of consumer decision-making based on principles of economics, assuming consumers are rational and self-interested individuals.

A framework used to understand how consumers make purchasing decisions, assuming that consumer behaviour is a response to various stimuli.

The series of steps consumers go through when deciding to purchase a product or service, typically including need recognition, information search, evaluation of alternatives, purchase decision, and post-purchase evaluation.

Classifications of consumer buying behaviours based on involvement level and perceived brand differences, including complex, dissonance-reducing, habitual, and variety-seeking behaviours.

A person's pattern of living as expressed through their activities, interests, and opinions (AIOs).

A theory explaining why people are driven by particular needs at specific times, arranged in a hierarchy from physiological needs to self-actualization.

A theory distinguishing between dissatisfiers (hygiene factors) and satisfiers (motivators) in consumer behaviour.

The tendency of consumers to notice stimuli that relate to their current needs or interests.

The tendency of people to interpret information in a way that supports their existing beliefs.

The tendency of individuals to remember information that aligns with their attitudes and beliefs.

The shared beliefs, values, customs, and behaviours of a group or society that influence consumer behaviour.

A framework for understanding cultural differences across countries and their impact on behaviour and values.